High Profile

Mortar the Point

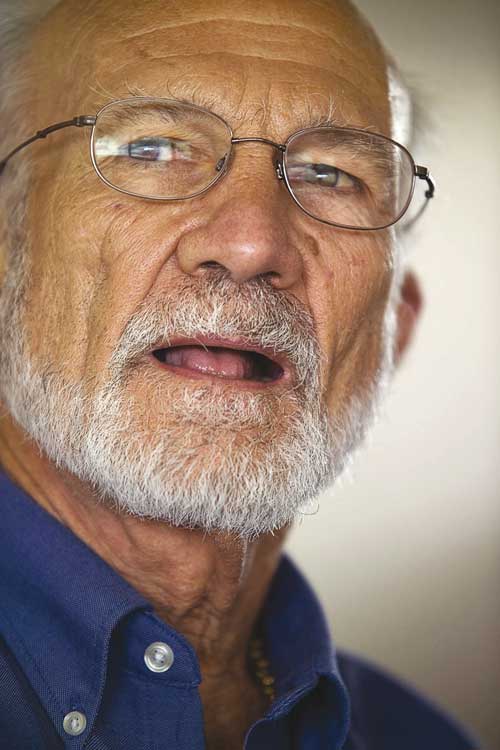

Interview by Luke Bretherton

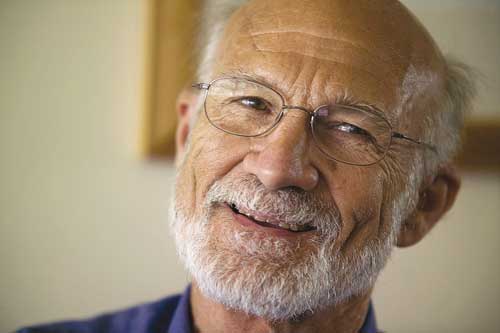

The son of a bricklayer, in 2001 Professor Stanley Hauerwas

was identified by Time as ‘America’s best

theologian’. Third Way did some bonding with him at the

Greenbelt Festival.

What does it mean to you to be a Texan?

To have an identity – and to have my life shaped by a

story – I haven’t chosen. Baylor University [in Waco] has on its

shield the motto Pro Ecclesia, pro Texana. Isn’t that wonderful?

The only ontological entities that matter! I think that the church

and Texas are the two realities that fundamentally determine my

life.

People in Britain often associate Texas with the redneck

right, but recently I’ve been reading a lot about the Southern

Populists. There is a radical side to Texas, too.

Yeah. Texas was settled very much by Tennessee folks,

just trying to survive on soil that doesn’t grow much, and Southern

Populism was our alternative to socialism. It could be quite

radical in its economic implications and quite conservative in its

social implications.

Could you be read as a Christian Populist, in that strict

sense of the term?

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. There’s a magazine called

the Texas Observer that was in the Populist tradition and

they were the radicals in Texas when I was in college. We all read

it and it had a big influence on me.

My father would not have known any of the writings of Populism,

but he certainly reflected that view.

You write very movingly about how as a boy you worked for

your father as an apprentice alongside your brothers. Can you say a

little about how their craft shaped your theological vision?

Well, when you’re initiated into a craft you have to

begin at the beginning and you have to learn all the subsidiary

skills that go with being a labourer. For example, when you learn

to chop mud – y’all call it ‘mortar’, we call it ‘mud’ – you have

to have a sense of the brick that the bricklayer’s going to lay,

because if he’s laying ‘common brick’, which is very porous, the

mud needs to be ‘loose’ (or wet), because the brick is going to

soak it up very quickly. If he’s laying ‘clinkers’ (which are

bricks taken from the bottom of the kiln, which are very hard),

then the mud has to be stiff. So, the labourer needs to know what

the bricklayer is going to confront. And there are numerous skills

like that.

I think that theology is like that. It requires training and you

have to submit to the authority of a master who has done it over

and over again. The master must know how to constantly readjust his

skills to new challenges, and that requires years of training.

My father was not only a master bricklayer, he was a master

stonemason, and I can’t tell you how hard it is to lay a stone wall

and have it look right. I mean, if you set all the big stones

together, or all the ones this colour, it looks like shit! It is

really an art. So, just the submission to someone who knows how to

do it, I think, is a nice analogy for what it means to be a

Christian, and what it means to be a Christian theologian.

And was that your experience of theological

training?

I think it was – you know, you learn that you can only

lay one brick at a time, and that is the way I do theology: one

brick at a time. I’m not clear even what it would mean to ever be

finished.

Bricklayers build houses, though…

They do, they do, and they’re finished. We theologians

are never finished.

You prefer to write essays rather than books and have

consciously tried to avoid constructing a systematic theology

–

Absolutely. I do, I do. Now, see –

– and yet you ended up (as it were) building a house

despite your best intentions.

I did, I did. But I think that the house that I’ve ended up with

needs a lot of work! And I have a lot of students that have picked

up some things from me who are continuing to work on the house in

quite creative ways that are going to change what it looks like.

This year they gave me a Festschrift.[1] It was very moving, but 18

of my students wrote essays that are all very critical and, you

know, I’m sympathetic to a lot of the criticisms.

One question is, well, how come someone so influenced by

Alasdair MacIntyre [2] takes John Howard Yoder [3] so seriously? I

think I’ve offered some answers to that but I don’t assume they’re

the last word and I recognise that there is a tension that I hope

will be fruitful…

You grew up a Methodist. How has Methodism left its stamp

on you? Is it a demon you’ve had to wrestle with, or an angel on

your shoulder?

It depends on what you mean by ‘Methodism’. There was a

movement within Methodism around the time I was coming through that

was represented by my mentor at Southwestern [University], John

Score, who argued that Wesley was much more a Catholic theologian

and that therefore to be a Methodist meant you were more Catholic

than the Anglicans. And I was persuaded by much of that.

Of course, that understanding of Methodism has almost nothing to

do with the reality of the Methodist Church! And so I’ve always

thought of myself as more Wesleyan.

Considering some of your theological commitments, it’s

sometimes said that you should have become a Roman Catholic – to

which you’ve always responded, ‘I’d be a Catholic if there was a

Catholic church to join.’ Could you unpack that a little?

Well, first of all I would never call into question a

person’s individual calling to think that they need to become a

Roman Catholic. I respect that. When Richard Neuhaus [4] was going

to become a Roman Catholic, there was this lovely moment when [his

fellow Lutheran] Robert Wilken was trying to talk him out of it and

said, ‘There are many rooms in our Father’s house, Richard.’ And

Richard said, ‘Yes, but some of them are better-furnished than

others’!

Now, I think Roman Catholicism is a better-furnished room, and

there are more resources there. In particular, I think its

resistance to capitalism has been quite remarkable – and also it

has probably been more resistant to nationalism than any of we

Protestants have been able to. I think that has a lot to do with

its ability to maintain patterns of authority that are not violent

(though sometimes they are), which has depended on a sense that

there is a tradition through which you think.

So, I’m a great admirer of much of Catholicism and I have deep

sympathies with it, and I can see how people could easily be called

into it; but I think it’s a church matter.

Rather than a matter of ‘You have to be in this church or

you’re not in the truth’?

That’s right. And what it means for Christian unity is

not for me to become a Roman Catholic but for us all, within the

worlds in which we find ourselves, to try to be as faithful to the

gospel as we can, and in the process hopefully we will be able to

look up one of these days and say: ‘We share a lot more than we

differ. Can we as churches recognise one another?’

And part of our task, by remaining Protestant, is to help the

Catholic church to be more catholic than we can be; and hopefully,

as we do that, the Catholic church will recognise us as worthy

brothers and sisters.

You have become an Anglican late in life. Some people may

see that as a short step from Methodism (given that it was

originally a movement to reform Anglicanism), but some have found

it surprising, given your critique of Christendom and the

established church. Can you say something about your journey?

Oh, I do think it’s in great continuity with Methodism,

and it has to do also, I think, with my formation through the hymns

of Charles Wesley. Wesley wrote, I think, the greatest Eucharistic

hymns in Christendom and singing them certainly shaped me through

my early years. I find those hymns best expressed through the

liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer, and therefore to be a

Book-of-Common-Prayer Anglican is my way of continuing to be a

Methodist.

But, let’s face it, we’re all Congregationalists now! We may not

like it, but we are. So, I could easily still be going to a

Methodist church if there existed a Methodist church in the area

in which I live that was Eucharistically determined; but there’s

not, and so I’m an Episcopalian because of the Church of the

Holy Family.

You know, I don’t pretend… I mean, how can any of us make sense

of our ecclesial status today?

Some of us just get stuck in the church we grew up

in…

Right, right! I tell my students: You oughta stay with

the people that harmed you!

‘Conversations’ with theological and philosophical friends

have been important to your development – one thinks of Yoder and

MacIntyre and others. What do you think makes for a really good

theological conversation?

Not being afraid of being in disagreement with one

another, so you learn from suddenly discovering that your friend

thinks things that never occurred to you and you are not sure what

to do with them! I think also working within recognisable reading

regimes, so that you both are trying to negotiate how to read this

book in relationship to that book. Reading together, I think, and

being ready to learn from one another, is really important.

I think also that you need work to do together – for example, to

write something together. Sometimes it can be quite difficult and

painful, but it can also be extreme-ly illuminating. If you

consider together the challenges before the church today and you

have a similar sense of what they are but maybe not of how to

respond to them, that can be very fruitful.

How does such a conversation work in practice? No one

would describe MacIntyre as an extrovert, and from your ‘memoir’,

Hannah’s Child, Yoder sounds interesting…

I’d say I’ve known two really big-brained people in my

life, Alasdair and John, and they are both very similar. They’re

both shy and a bit introverted and can be quite brutal in their

responses. I think that’s part of the price of having such a big

brain. But both Alasdair and John have – John had, Alasdair has – a

wonderful sense of humour, and you can never forget they’re human

beings and therefore they value our friendship, although they may

not always know how to express it. And so I’m determined not to let

them intimidate me – though they do – because I think that they

need friends, and I certainly need their friendship.

When I told John I was leaving Notre Dame [University], we’d

known one another 10, 15 years but I had no idea how he really

regarded me. And he misted up. I was really taken aback. I realised

that I meant a great deal to him, and I value that.

Some of your conversations have come to an abrupt end.

What makes further dialogue impossible?

When the neoconservatives at First Things said that

pacifists have nothing to say about [‘the war on terror’ and the

war in Iraq], I just realised that these folks (who I have a great

admiration for in many ways) had never bothered to really

understand Yoder! And they weren’t going to. I mean, they just need

to read [his book The] Christian Witness to the State. And

I just wasn’t interested in continuing that conversation any more:

their habits of mind were set and I had other fish to fry, so to

speak.

Jean [Bethke Elshtain] [5] I admired and my relationship with

her was much more personal in a way, and when Paul Griffiths and I

wrote that really fairly sharp review [of her Just War against

Terror] – I mean, I didn’t mean to hurt her but we did, and I would

hope that – I mean, we are very civil with one another. I just

don’t know that we have that much to say to one another.

You are well known as a pacifist, following Yoder. How do

you feel about the continuing co-option by so many in the United

States of Christian language – for example, of sacrifice – in the

cause of the ‘war on terror’?

I’ve got a book coming out called War and the

American Difference: A Christian alternative, and in it I say

– you know, just war, pacifism, we’ve thought through them to death

and either one would place a severe limit on war, but yet we

continue to have war, particularly in America, and why is that? I

think war is such a morally powerful practice, and in particular it

is the practice of sacrifice; and America’s a country that cannot

live without sacrificing its youth periodically to show that we

are worthy of the sacrifices of the youth in the past.

So, war is ritualistically required from time to time in order

to renew America’s moral capital. And one of the greatest

sacrifices [required] is not simply the sacrifice of possibly

losing your life or your friend but the sacrifice of your normal

unwillingness to kill. And doing that and – even if you don’t kill

– envisioning killing I think creates a silence around us that is

very hard to know how to live with. And we expect those who have

fought in war never to tell us about the reality of it. War must be

turned into a heroic tale, rather than the truth that it is dumb

boys killing dumb boys.

That Christians in America don’t call into question the

co-option of their language by civil religion I think is absolutely

puzzling, just amazing. I was called up by Time about the arguments

about the [so-called Ground Zero] mosque in New York City and I

said, ‘Why would anyone think that the World Trade Center site is

sacred?’ Where the hell did that language come from? I mean, God is

holy and makes places holy. That was murder, and the people that

were killed there were victims, they weren’t martyrs!

You once said of Karl Barth that he would have been a

better theologian if he had read more Trollope. Can you name some

novels that you think are essential reading for a theological

vision? And say why?

Well… Crime and Punishment. Dostoevsky looked into the

heart of the world that was [in the process of being born] and, I

think, saw clearly how it made Christianity unintelligible to

itself. And of course to look into the heart of that world was also

just to look into the heart. He saw the terror.

(The novel is, of course, a recent development and it is the

fundamental bourgeois art form – I suppose you could say the movies

are more now. Once the church was no longer able to sustain a

casuistical tradition, the novel becomes a kind of casuistical

tradition in which we explore the possibilities of life as we now

find it.)

Besides Dostoevsky, I think George Eliot’s Middlemarch

is – I like Adam Bede better, but Middlemarch is clearly

more ambitious and more probing. Of course, I think Trollope’s just

brilliant – the Palliser novels rather than Barchester

Towers, I think.

Obviously, Joyce’s Ulysses. Of course I learnt a hell

of a lot from Iris Murdoch’s novels, and in particular I like

The Sea, the Sea. In America, I think John Updike is

extraordinary for the exposure of our lives and… And of recent

novelists I think you just have to read John Banville, because he,

as far as I can tell, doesn’t believe in anything and yet he writes

damn good stories. How do you write a good story if you are a

committed nihilist? So, I think Banville is certainly

important.

One reading of a lot of contemporary US literature is that

it is precisely when you stop believing in the gospel that you

become obsessed with sex and death – Philip Roth being the obvious

example.

Right. Right. I like Roth a lot.

But most of the novelists you have mentioned were

thoroughly steeped in the gospel…

That’s true. Eliot, even though she wasn’t a Christian –

my goodness! she knew well, and had an opinion on, the fundamental

narrative of the gospel.

Do you think there are the same resources in cinema?

No. No. Cinema really is the great democratic art form,

because it lets you see without requiring work.

When did you realise that you were an icon? And how do you

handle being ‘Stanley Hauerwas’ when you write?

I only realised it, I suppose, in the last 10 years,

maybe even less than that. I’ve just become a figure that people

need that may have something to do with who I am but very

accidentally. One of the reasons I wrote Hannah’s Child was

exactly to demythologise that icon, because I want to remind

people: I’m a human being and I’m just trying to muddle through!

And I’m trying to help us each muddle through.

People want you to be wise and, you know, I’m a working-class

kid, I don’t want to disappoint people! But it is unrealistic to

think that you’re always going to be wise, because if you play that

game you never learn and you have to be ready to learn… You know,

that’s a hard negotiation.

But I don’t think I will ever be an icon the way that Reinhold

Niebuhr [6] was – for two reasons. One, ‘Hauerwas’ is so hard to

say compared with ‘Niebuhr’! And, two, his iconic status has

everything to do with a still intact Protestantism, whereas our

loss of a Protestant space and a sense that we can go to the State

Department [as of right] I think means that whatever ‘Hauerwas’

may stand for cannot be sustained in the way the Niebuhrian

iconic status can.

I suppose another way to express the iconic thing is fame, and I

have to say I find it unbelievably tiresome! You can say, ‘Well,

that’s because you’ve got it,’ but, you know, I’m happiest when I’m

talking with someone like you or in a seminar with my graduate

students or at home watching the [Atlanta] Braves with my wife, and

I don’t think I need it. I hope I don’t, because I’ve decided to

retire in three years and that feels damn good to me. I think what

saves me from fame is friendship, and as long as I still have

friends, that means a hell of a lot. So, that’s the way I think

about these matters.

What about when you’re writing? Do you ever think, ‘How

will this affect how people perceive Stanley Hauerwas?’, rather

than just being true to yourself as a thinker and writer?

I think that when I’m writing (which is most of my life)

I’m never sure I know what I am doing until I do it. But I’ve tried

to maintain a high standard in everything I do. The temptation is

to think, ‘Oh, I can just dash this off because I’m Stanley

Hauerwas,’ but I’ve never given in to that temptation – I hope

I’ve never given in to it – because I think that every forward I

write, every book review I write, every essay I write, every book I

write, has to be the very best I can do.

It comes back to bricklaying.

It does. But also when you’ve got an unfinished position,

you need to use each request to write this or that to force you to

say what you think needs to be said that you haven’t said by what

you have said! And so I try to discover what I should think, given

what I have thought, that I didn’t know I thought. And that comes

through writing, and it comes through exchanges – and that’s why

writing is always work.

But I worry now that there’s so much Hauerwas out there. You

know, you don’t want to burden people. I’m not compelled to just

get more out there, but I am compelled to continue to think, and

the way that I think is by writing and so I just keep writing. What

I really like to do now more than anything is to write sermons. I

find it the most intellectually challenging activity that I do,

because you need to keep it short and you need to submit to

scripture – and I really like that.

The hard thing about writing sermons is, they require you

to be both intelligible and succinct.

Absolutely.

What are some of the writing vices of theologians?

The use of the subjunctive! And the use of the passive

voice. You’ve got to use active verbs.

I think many theologians write in a way not to be

understood.

Deliberately?

Deliberately. I mean, obscurity is thought to be a sign

of profundity. That’s just bullshit. I think it’s important to

write directly and not to be afraid of assertion. This is

proclamation.

What I find astounding in Niebuhr is the clarity and

crispness of his thought, which is why people still read him. I

think that is a lost art in theology today.

Who do you think I learnt it from? I mean, no one’s read

more Reinhold Niebuhr than I have. I’ve read the lot! It was from

Reinhold Niebuhr that I learnt the necessity and importance of the

aphorism. ‘The church does not have a social ethic; the church is a

social ethic,’ that kind of thing.

It’s taken me a long time to realise that it takes an

awful lot of thought –

It takes a hell of a lot of thought.

– and creativity to come up with them.

‘The first task of the church is not to make the world

more just but to make the world the world.’ That took a hell of a

lot of work! Of course people say, ‘Well, that’s an

oversimplification.’ Yes, but…

But I think, as with Jesus’ aphorisms, there’s a difference

between being simple and being simplistic.

What was it Niebuhr said? ‘Man’s capacity for justice makes

democracy possible; but man’s inclination to injustice makes

democracy necessary.’ [7] I think that is ingenious. And wrong.

But you’ve really got to appreciate its ingenuity!

NOTES

1 A collection of original essays written by close

colleagues, students or other admirers to honour an academic or

other eminent person

2 Scottish philosopher and Catholic theologian best known

for his 1981 book After Virtue

3 US Mennonite theologian, ethicist and biblical scholar

best known for his 1972 book The Politics of Jesus. He

died in 1997.

4 US theologian who began as a Lutheran who marched with

Martin Luther King and ended as a Catholic who mentored George

W Bush and helped to forge the evangelical-Catholic alliance that

brought him to power. In 1990, he founded the ecumenical journal

First Things, whose stated aim is ‘to advance a religiously

informed public philosophy for the ordering of society’. He died

last year.

5 US political philosopher and Lutheran theologian

6 US theologian who was a key intellectual of the Cold War

era

7 From The Children of Light and the Children of

Darkness (1944)